Some specimens may be very tiny; on the order of less than 0.1 cm. Some preparation methods employ the use of mesh cassettes, “tea bag” biopsy pouches, sponges, wrapping paper, etc. to contain the specimen and prevent it from escaping the tissue processing cassette. A disadvantage of the above methods is that upon embedding, the specimen must be handled yet again, possibly resulting in additional fragmentation of the tissue, or possibly complete tissue loss. These are among the most difficult specimens to troubleshoot, as the most common suboptimal event is: where is the tissue that is supposed to be on the slide? Did it survive processing? Did it escape the processing cassette? Did it fragment during embedding? This blog will examine several methods of dealing with tiny specimens, such that each and every one received in your lab ends up on a microscope slide.

A proper method of using wrapping papers is described by Dr. IB Dimenstein. This method works very well for fragile tissues such as prostate and breast needle biopsies. Dr. Dimenstein notes that the use of sponges/polyester pads may result in a ‘compression artefact”, which can occur during processing. Specifically, tissue needle biopsies may compress and narrow, comparable to the size of the pad mesh holes. One solution is to lay out and wrap the core in lens paper, and then sandwich the wrapped specimen between two sponges, which have been pre-soaked in formalin.

Regarding core fragments remaining in the specimen bottle, Dr. Dimenstein recommends filtration through a porous paper, such as the internal layer of a Kimberly-Clark protective mask. This is more reliable than trying to remove fragments with a pipette, where mucous or tiny fragments may stick to the inside of the pipette. He does not recommend filtration through nylon mesh bags, as the tiny fragments are difficult to retrieve during embedding.

When embedding these specimens, Dr. Dimenstein recommends the use of a tamper to flatten the core, to keep it parallel to the block face. If two cores are present, they should be embedded parallel to each other, and to the horizontal axis of the block. Filtration specimens should be embedded in the manner similar to embedding any aggregate of tissue, carefully grouping the fragments into the middle of the mold.

In addition to the above method, Sakura Finetek makes a product called Tissue-Tek Paraform Tissue Orientation Gels that can be used in conjunction with their Paraform cassettes. This material can be used to hold small specimens in place and in proper orientation, from grossing through embedding.

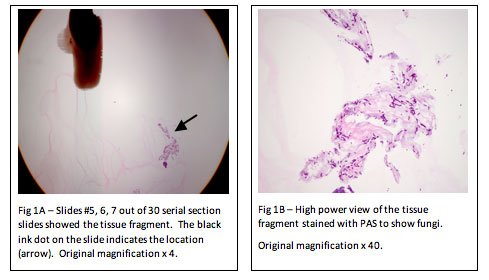

An alternative method is to use a product called “HistoGel”. HistoGel is a liquid at 55℃ and has a gelatin consistency at room temperature. The idea is simply to surround the tiny tissue fragment(s) with liquefied HistoGel and allow it to cool to room temperature (approximately two minutes), thereby trapping the tissue fragment in the HistoGel, much the same way fruit is embedded in the gelatin of a Jell-O fruit mold. The resulting “button” of HistoGel containing the tissue is placed into a tissue processing cassette and processed as usual. (Note: do not use microwave processing, or “Rush” processing.) During embedding, the button is simply removed from the cassette and embedded as usual. Additional slides may have to be taken to reach the fragment embedded in the HistoGel; however, the tissue cannot be lost in processing (Figure 1A, 1B). This process far outweighs the extra effort involved during the surgical grossing procedure.

In summary, it is excellent practice to identify all specimens that may be received by your laboratory for “non-routine” histology. Once identified, procedures should be developed for proper receipt and handling of the specimens. This is the only way to ensure the highest patient care quality and to avoid later instances of troubleshooting sub-optimal events.

REFERENCES:

- Chapman, C.M. (2017). The Histology Handbook: In Search of the Perfect Microslide. Amazon CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Chapman, C.M. and Dimenstein, I.B. (2016). Dermatopathology Laboratory Techniques. Amazon CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Dimenstein, I.B. (March 2016). Technical Note. Submitted to J Histotechnol (Vol.39(3): 76-80)

- Chapman, C.M. (2018). Troubleshooting in the Histology Laboratory. Submitted to J Histotechnol